Twilight of art

Serhii Lykov’s metaphorical meditations

Odesa — “Selected” is the title of the exhibit of the conceptualist, new-wave artist Serhii Lykov, launched in Odesa’s Museum of Contemporary Art. In the early 2000s this artist took part in Kyiv’s exhibits (galleries Irena and L-Art, Museum of Contemporary Art, Central House of Artist) and se-veral international projects. Lykov’s new private exhibit, following the organizers’ intent, is of retrospective nature: the works on display cover practically the entire creative period of the 50-year-old artist.

Lykov is an Odesite aesthete-artist and culture expert. He thinks in a broad and cyclical way. His artistic results create a virtual, but self-sufficient world, accumulating the historical experience of humankind. The artist’s task is to embrace and rethink this experience, delineating it at an individual level. All ideas, images, and thoughts find absolute completeness and fullness of expression. Only accents and combinations vary. His paintings have become museum items which exist autonomously and wander in space and time, gaining greater charisma and new sounding in its context.

Lykov became known for his openly postmodernist work Baroque Concert (1987), a sarcastic-ironic piece and a sort of a theater of absurd. Other pictures, united in a cycle “Wild Shadows of Love” (1995), are a series of interior compositions, borne by the urban reality. In the works from this period one can feel a certain hesitation, vagueness, and therefore the material world looks somewhat uncertain in his works. This is sheer neo-Platonism with its primacy of an idea where all material things are temporary: actual things immediately turn into past, reminiscence, a dream.

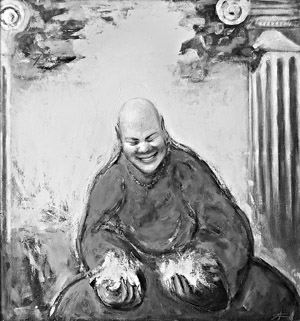

In many of his works the artist applies a meditative approach: suffice it to mention another cycle of the artist’s metaphorical pictures, for example “Catchers of Dreams” (2007-08). In his art Lykov tries to unite different civilizations – the European and Eastern one, but he is also an idealist and romantic in this. Lykov’s creative work is of irrational nature and cosmopolitan coloring. The explanation should be found also in his delight with the teaching of Mexican shaman of Indian origin Don Juan Matus. In this respect turning to the epoch of early baroque is also a sort of romantic retrospection, not without pretension (maybe even snobbism). I am not sure that he does this deliberately, but his passion for all things oriental has a rather destructive effect, which leaves less room for faith in the myth cultivated by Europeans for the previous two millennia (“Caravaggio’s Mistrust,” 2007). However, the artist himself admits that in the series “Caravaggio’s Mistrust” he did not set himself global tasks – this is only a dialog with Caravaggio himself, who created his own myth. I want to note that in the works of this cycle the mise-en-scenes are constructed in a convincing manner, the characters’ gestures and facial expressions are very distinctive.

The question arises: do we have the right to ruin the structure of this unconvincing, from the viewpoint of the 21st century man, yet integral spiritual world, which was sincerely created by, for example, Michelangelo or Caravaggio? Isn’t it better to create a world of one’s own? Many of Odesa’s postmodernists followed this path, in particular Viktor Pavlov and Oleksandr Roitburd (who studied together with Lykov). After all, this “dialog” of the modern artist, with his outstanding predecessor, the new Gnostic structure of spiritual space, is being created as a deconstruction of the Renaissance understanding of Christianity. The word “dialog,” one must admit, sounds somewhat pretentious, even mystical. Thus, interpretation may be a more appropriate term, because the author himself, just as the thoughtful, well-prepared audience, will answer Caravaggio’s question. But this approach broadens the functional connections of Caravaggio’s works as an artifact owing to its potential interpretation. Lykov introduces a game aspect, by showing, like Caravaggio, his own portrait and those of his contemporaries. Whereas in the early 20th century the discovery of the Shroud of Turin strengthened religiousness in the Christian world, nowadays the discovery of the apocryphal Gospel from Judas is rather putting it to the test and weakening the fragile faith. Maybe it’s for this reason that some critics, who uphold orthodox standpoints, perceive Lykov’s interpretation unfavorably and blame him for infringing on the foundations of Christian teaching. These people were especially outraged by the use of the geisha’s image in this composition (hinted by Maria Magdalena’s image). Our society of today is pluralist, and not always tolerant. After all, Caravaggio’s contemporaries also did not accept his religious works, considering them too naturalistic, folksy and “modern.”

It should be admitted that unlike modernists, this artist does not regard the shape an end in itself. In this respect he is conservative enough and cultivates formal completeness. Such were the foundations laid in the artistic-graphical department of the Ushinsky University, which Lykov graduated from in 1985. His teachers included one of the department’s founders and its first dean Valerii Hehamian, as well as Stroganov Aca-demy graduate Zinaida Borysiuk. Hehamian considered that full-fledged creative work is not possible unless fundamental knowledge of craft and broad culture outlook. I should admit that among all renowned students of Hehamian, it was Lykov who mastered his teacher’s graphical system in the most consistent manner, which cannot be said about his paintings – they are too speculative. But the artist aptly used the strong sides of his talent and created an eclectic yet logical expressive graphic-painting system, whose peculiarities vary depending on the topic. For example, in the series “Illustrated World History” (2001), with its hierarchical nature and “frieze” approach, the rhythm which develops not only along the plain, but in the plain as well, is important. In this series the artist, being a consistent postmodernist, showed masterful usage of the pop-art methods and stylistics of ancient art, specifically Egyptian and Babylonian. “In this history of culture any crisis is a simultaneous death and birth of new structures of apprehending the world and attitudes to it,” as the author himself explained.

In the cycles “Catchers of Dreams,” “Roads,” and “Caravaggio’s Mistrust” the artist uses the effects associated with computer graphics: dimness, soft transitions of local co-lors, turbulence and spherical effects etc. This anthropogenic nature, running counter to conceptual conditionality, does not always look convincing. This does not refer to “Caravaggio’s Mistrust” or, for example, the previously mentioned “anti-clerical” work Baroque Concert. The artist’s passion for effects is not an end in itself: it is motivated by content, though in separate cases it balances on the verge of salon-style because of its intentionality. We also know of wonderful examples of this art born by scholasticism, for example those by Henryk Siemiradzki or Paul Leroy (their works decorate one of the halls of Odesa’s Museum of Western and Eastern Art). As an aesthete-artist, Lykov treats the classical heritage with awe, getting additional creative impulses in the museum halls enveloped with the patina of time. Symptomatically, the exhibit of the works of the cycle “Caravaggio’s Mistrust” took place in the Italian hall next to Caravaggio’s famous picture The Taking of Christ. Other means are quite traditional: contre-jour, night contrast lighting – these methods were applied, besides Caravaggio, by French (George de La Tour) and Dutch painters (Gerard van Honthorst). The artist showed his richness of formal approaches and technical versatility in the abovementioned series “Catchers of Dreams” – from academic drawing to symbol-imaginative meditations to impulsively expressive compositions.

As a consistent postmodernist, Lykov likes to add some text to his works, such as press reviews, which give a guideline for the audience. “If the works prompt some feelings and thoughts in the audience – the creative act goes on. It is not so important how different is the primary author’s message and the audience’s further interpretation. Personally I think that creative continuation of meditation on given topic is particularly important,” the artist explains his mission. Currently Lykov has found his audience, he has admirers among the art connoisseurs, fellow artists and museum employees. And the new exhibit of the artist is further proof of this.