An Unpardonable Ailment

The Ukrainian countryside was suffocating in the deadly embrace of collectivization. The intelligentsia either hid or ardently cooperated with the NKVD, reporting on friends and relatives in order to survive. The press thunderously branded and condemned kulaks and "wreckers," among them bourgeois nationalists, of course. One by one the poet's friends vanished in the bottomless NKVD basement at the former Institute for Girls of Noble Birth.

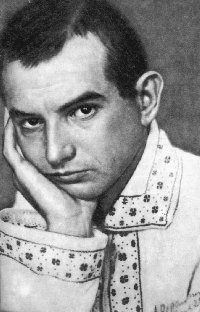

Sergei Kirov was shot in Leningrad on December 1 and the very next day an edict was published, prescribing "extraordinary measures" to combat "terrorists and counterrevolutionaries." On the night of December 4-5, Felix Dzerzhinsky's (whose towering statue the Red Russian Duma plans to reinstall in Moscow) tireless bloodhounds arrested poet Yevhen Pluzhnyk, along with a dozen other authors as "literary terrorists, versifying spies, and philological diversionists." When interrogated, the poet did not even try to refute the absurd accusations and confessed to everything, so the humane communist blind justice magnanimously commuted the usual death verdict to ten years in the formidable Solovetski Islands concentration camp. Pluzhnyk was already suffering terminal tuberculosis and did not really care one way or the other, although he did live another year before his bones were added to the foundations of that bright socialist future from which we have still to extricate ourselves.

As a rule, a prominent poet can foretell his own death. Pluzhnyk, after living through the horrors of civil war, working as a schoolteacher in Poltava oblast, having inherited the incurable disease from his mother (as did all his brothers), was especially keenly aware of life. And death. He regarded the latter with something akin to stoical aloofness. "More and more often I dream of a snow desert," he wrote in the early 1930s, like an old sage, and only a very perceptive analyst could detect the sharp emotionality of a young man who loved life so much (he was 37 when he died in the camp).

In fact, Pluzhnyk's entire creative period was only a decade, if we disregard his early verse written in Russian while in high school and lost forever. His first Ukrainian poems were carried by newspapers in 1923-24. In 1926-27, he published two collections of verse, Days and Early Autumn, which confirmed beyond doubt his reputation as a first-rate poet despite increasingly sharp attacks in Party-controlled periodicals; they did not like his pessimism and apolitical nature. Least of all they liked the poet's inborn humanness which they branded as abstract humanism.

The social climate at the period in no way fostered literary talent, yet Pluzhnyk took up a professional literary career. In 1928, he wrote the novel Ailment (1929 saw a second printing) and several plays (none would be staged). He translated from Chekhov, Gogol, Gorky, and Sholokhov (in fact, he was arrested when working on the galleys of the second book of The Quiet Don, known in English as the second half of And Quiet Flows the Don. His Ukrainian version would be published without identifying the translator). Finally, together with Valeryan Pidmohylny, he compiled a Russian-Ukrainian Business Dictionary to be reprinted several times, including in independent Ukraine. Ironically, Pluzhnyk would find himself in the same prison cell with M. Darmoros, co-author of a Dictionary of Technical Terminology, apparently another inveterate "terrorist and counterrevolutionary").

Yevhen Pluzhnyk's third collection of verse, Balance, written in 1933, was never published in the USSR. Fortunately, the manuscript survived and appeared in print in Augsburg (1948). Two other collections were published in Munich (1979). It is hard to believe today that all this melancholic verse, full of premonition and philosophically aloof, was not only written in the early 1930s but also officially submitted for publication ("And again there will be: two meridians, two parallels, a rectangular paradise"; "My soul! You are again on the verge ... Then will come journeys in transparent haze..."). A selection of his verse was published in Ukraine in 1966, after partially rehabilitating his name as "unjustly purged." Finally, his entire literary heritage appeared in print in 1988, in the Poet's Library series, with Leonid Cherevatenko's excellent introduction. In 1992, largely thanks to Mr. Cherevatenko, Pluzhnyk's novel Ailment and three surviving plays were reprinted. It seems, however, that Pluzhnyk with his "abstract humanism" and profoundly tragic metaphysical Weltanschauung, is as incompatible with our age of state building as it was with the preceding socialist paradise. The fact remains that the good old classics of socialist realism predominate in academic papers and school textbooks.

"I represent a sad phenomenon," says poet Vyhorsky in Pidmohylny's brilliant

novel, The City (the author is said to have used his friend Pluzhnyk

as the model for its hero). "Sadly, two ages are inevitably connected by

people hanging suspended over the line separating that which was from that

which is to be. From where they hang one has a good view back and forward.

In other words, they are afflicted with an ailment which no party will

ever forgive, eyesight too keen."