“Caricature is a free opinion which scares the regime very much”

Viktor Bogorad on the past, present, and future of exposing laughter

We used to have Perets (Pepper) and the Russians, Krokodil (Crocodile) [satire and humor magazines in the Soviet time. – Ed.]. Both rest in peace now. Over the two recent decades the caricature has been losing grounds and is making increasingly fewer appearances on newspapers’ pages. Why? They say that a caricature, especially political, lives only one day. Nevertheless, The Day’s example proves the opposite. Anatolii Kazansky’s cartoons, made decades ago, continue to appear on its pages, since they remain topical. Moreover, an album of Kazansky’s cartoons, published by The Day, still enjoys great popularity. As Larysa Ivshyna said in the foreword, “his drawings have pushed through the time. They have turned into images, deep metaphors which even now, years after, show us new facets of his thought. And again they go out to the reader.”

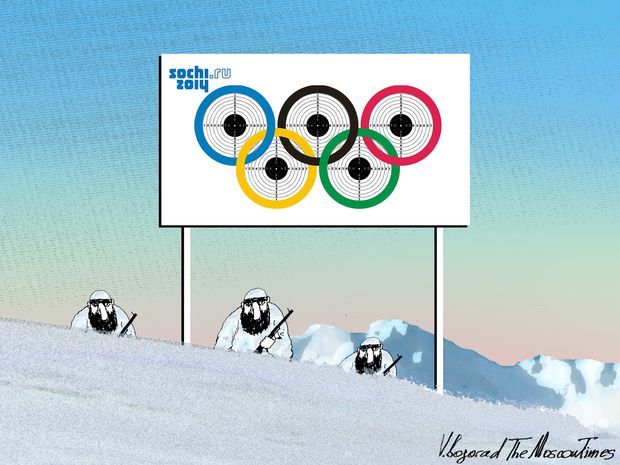

The decay of this humoristic subtype of fine arts is perhaps caused not by censorship, and even not by the printed media’s new preferences, but by the lack of artists who could see much further beyond their epoch. Russian Viktor Bogorad is just one of such cartoonists, whose drawings have stood the time and laugh tests by a few generations. He is a pupil of the Soviet school of caricature, and at the same time a man with an absolutely un-Soviet thinking. The Day has interviewed Bogorad about the prospects of political humoristic drawing in Russia and worldwide, untranslatable meanings, the noticeable absence of cartoons showing the governor of Saint Petersburg, and the reaction of the high and mighty to exposing laughter.

You published your first cartoon 40 years ago [the first was published in the magazine Avrora in 1973. – Author]. This is almost half a century ago. In what way have your drawings changed?

“In 1973 I did not draw political cartoons for obvious reasons. I did not want to engage in propaganda, as I held unorthodox views. But when I worked in the newspaper Smena, I began to make political drawings. From 1988 to 1992, the front page carried my domestic policy-themed drawing every day. It was the first Soviet youth newspaper to do so. By the way, Georgii Urushadze was one of our correspondents who sat on the commission investigating the coup d’etat. Later he wrote a whole book on the subject, Izbrannyie mesta iz perepiski s vragami (Selected Extracts from Correspondence with My Enemies) and illustrated with my cartoons from editorials.”

And how did the newspaper come out during the putsch?

“We kept working no matter what. I was at the office, drawing pictures featuring the putschists. I believe it was the only issue that was published uncensored. With an eye-catching headline ‘Nobel Prize to Whoever Arrests Yanayev.’ Large stacks of this issue were carried away to other cities. Our office received many nice letters, which we had to burn later. At night, we pasted the newspaper on the shop windows in our own city. I kept the watch. Never before had I dreamt to be a guerilla fighter. Our papers hung there for days, while the military pondered whose side to choose.”

NOT ALL MEDIA ARE EQUAL IN THE EYES OF THE GOVERNMENT

How dangerous is the caricature as a genre in today’s Russia?

“About a year ago I got a phone call from a female journalist from France Press, who asked me, ‘Is there political caricature in Russia?’ I answered with a question, when did she last see a cartoon of the governor of Saint Petersburg? She could not recall, but I know that it never existed, in the first place. And then I got a call from Russia TV Channel. They said they had seen my interview and wanted to talk to me about it. I agreed and gave them an hour-long interview, only to see that they published the most innocent 15 seconds of my speech. If you draw political cartoons, you are prepared to face different reactions. In other words, the editor is aware that if they decide to print a political cartoon today, tomorrow either the whole office will have to look for a new job, or the issue never gets published. But not all media are equal in the eyes of the government. For instance, I make drawings (on Ukrainian themes as well) for the Moscow Times. This is an Anglophone periodical for international readers in Moscow, which should make it an independent media. But in the eyes of the government, the newspaper is of little consequence since it does not have a huge circulation.”

You have been working for the Moscow Times for 20 years now. How do you translate Russian reality for the Anglophone audience?

“I should say that this is a big problem. It has a different mentality and a different sense of humor. I learn every day. You have to be born in the West to be a Western cartoonist. You have to know some basics. For example, a reverted V-sign will mean a call to violence. Or, if you kiss a frog in a fairy-tale, we expect it to turn into a princess, while for a Westerner it will turn into a prince.

“I recall that when Yeltsin came up with the idea of a tripartite alliance of Russia, Belarus, and Yugoslavia, I got a commission for a cartoon on this topic. I used the plot of Jerome K. Jerome’s Three Men in a Boat, to which an Englishman says that this author is unknown to their audience. Ok, then I draw the Three Wise Men of Gotham (this English folk song was translated into Russian by Samuel Marshak). But this image seems to ring no bell either. So eventually I had to resort to the Three Wise Monkeys, covering their ears, mouth, and eyes.”

Western cartoonists often use captions to make their drawings clear for bigger audiences. Do you use captions?

“I try to avoid them in my cartoons. Once the renowned American cartoonist John Michael Callahan brought his exhibit over to Russia. He held a master class, where he said that he was very happy when he managed to make a drawing without text. This is the typical modern American cartoon: with inscriptions, speech bubbles, captions, etc. On hearing this, Russian cartoonists only grinned: we make textless drawings on a daily basis. Captions, idioms in particular, are tricky and hard to translate. The word for word translation of the idiom ‘my house is on the outskirts’ [meaning ‘it’s no concern of mine.’ – Ed.] will say nothing to an American.”

POLITICAL CARTOONS LIVE BUT ONE DAY

Can caricature, or a particular cartoon, become obsolete? And can one make a cartoon which would ring a bell to at least three generations?

“Political caricature becomes outdated very fast. A newspaper’s life lasts but one day, and the same is true for a political cartoon. Everyday life caricature, rooted in today’s realities, also becomes obsolete in no time: say, who recalls ration cards now? Images based on an individual’s idiosyncratic thinking are more long-lived.”

How do you come up with your drawings?

“It is inexplicable. You get a brainwave – you can see a picture, you only need to draw it. However, I have some taboos. I avoid the themes of religion and ethnic conflicts. When a cartoonist does something of this kind, he becomes a propagandist, he takes a side in the conflict. Let’s take the Karabakh conflict, for instance [an ethno-political conflict in the Caucasus between Azerbaijani and Armenians. – Author]. In this situation a cartoon will only add fuel to the fire. Yet one has to take into account the fact that different cartoonists have different political preferences. Mine can be seen through my cartoons.”

The Day’s Press Club published your cartoon, when both we and you shared interest in an opinion poll done by Dozhd TV station and in the further course of events. Do you follow the developments in Ukraine, including the recent ones? What is your reaction to them?

“I do react, but my responses are only printed by the Moscow Times. Other Russian papers prefer to ignore the topic or get away with some officialese. In our countries caricature is a free opinion which scares the regime very much.”

Do you know any representatives of the Ukrainian cartoon school?

“Yes, I have a pretty good idea of your school. I even was invited to take part in an exhibit in Kyiv past year. Ukraine has a very strong cartoon school. Volodymyr Kazanevsky alone has an impressive harvest of prizes. Alas, Yurii Kosobukin is already deceased. I knew him very well, and I even published his book in the series ‘Master Cartoonists’ Gallery.’ We have already published some 30 albums, but Yurii’s work was the first to appear. And it was also his first book, because not a single copy had been printed in Ukraine. When I was in Kyiv, I talked to his son. He does not know what he should do with all those drawings, prizes, and awards. You do not have a caricature museum. Nor do we, for that matter.”

“WE DO NOT HAVE ONE COLLEGE WHERE THEY TEACH CARICATURE”

Does the modern Russian caricature display the tendency towards dividing into schools, making use of the traditions, or do artists work on their own?

“As far as schools go, even now there still are people who keep drawing in the Krokodil style. Unfortunately, we do not have one college where they teach caricature, although the genre has its own rules. The situation in the West is quite different, but it may be due to a developed comic strip culture, which did not take root in our soil. To become a true professional, a cartoonist has to read a lot and watch good films. If you do not become a philosopher, you will become a cartoonist.

“On the whole, cartoonists are terrible individualists. But thanks to the existence of various clubs and associations, we still stick together. Two years ago the Nuance [a group of caricaturists made up by Bogorad, Viacheslav Shilov, and now deceased Leonid Melnik. – Author] held a big exhibit. My personal exhibit ‘Inaki’ took place a year ago at the Non-Conformist Art Museum, Saint Petersburg.”

There was a very busy period in your life, when you held a lot of exhibitions [at Gallery 10-10 in Leningrad; Zurich in 1990; Schwyz, Switzerland, 1991 – Author]. What caused such a big demand for cartoons back then?

“Perestroika enabled me to make my first trip abroad in 1987. Then followed the after-putsch period, when many expected Russia to become a democracy. This spurred a great interest in both the country and its representatives. But alas…”

What are the prospects of caricature, especially in Russia?

“Caricature can only survive if some political ingredient of today changes. Unfortunately, now I do not have a personal column as a cartoonist, but I would very much like to return to that format, because it offers such freedom.”