The Chronicles of Great Utopia

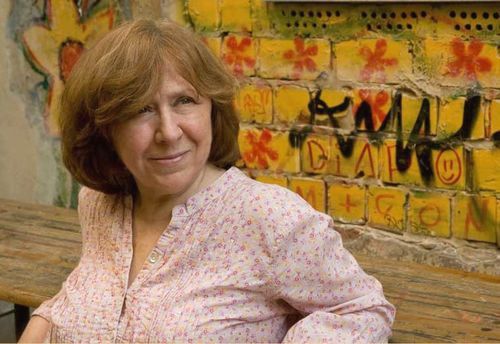

Svetlana ALEXIEVICH: “A Soviet person has no self-responsibility; it is a mix of prison and kindergarten”

Belarusian writer Svetlana Alexievich finished her pentalogy on the Red Empire, which she has been working on for 35 years. It includes The Last Witnesses: The Book of Unchildlike Stories, Zinky Boys: Soviet Voices from the Afghanistan War, Enchanted with Death, The Chernobyl Prayer: A Chronicle of Future, and the last part of the pentalogy, Second-Hand Time will soon be published. The author spent years gathering the evidence of the war and witnesses of the catastrophes, she lived through thousands of stories trying to look into the essence of the Soviet citizen. Alexievich is considered to be the first representative of “documentary fiction,” though the author herself prefers a name “the human voices genre.” This is a person who knows the face of Chornobyl and war. This is a journalist who has been through court proceedings and political pressure in Belarus. She traveled across Europe for a long time, living in Italy, France, Germany, and Sweden. Finally she came back to Belarus. But first of all, this is a frank and strong woman who remembers about humaneness and values.

We met her during the Sweden-Belarus Days “Literary Journey: Belarus,” which due to the problems with Belarus visas for Swedish masterminds and strenuous diplomatic situation between Belarus and Sweden were carried out on a sort of no man’s land, in Lviv. By the way, the author herself was born in Ivano-Frankivsk, where she nearly starved to death at the age of two. This fact is too befuddling to leave it unexplained. Alexievich shared with The Day a lot of memories from her personal life, talked about her own experience of meeting war and Chornobyl victims, about the restoration of Belarusian identity and ghettoization of Belarusian intellectuals. She also told about the project of her whole life, exploration of the “Red person.”

You are often called the “Chronicler of Great Utopia,” but in your book The Chernobyl’s Prayer: A Chronicle of Future you say that you are “the witness of events, equal to others.” What did you feel when you talked to victims of war and witnesses of catastrophes? Did you try to walk in their shoes?

“I would not be able to tell about my life as openly as protagonists of my stories did. I am grateful to them, and I’m even surprised at the courage with which they told about all their pain. But relations with them can sometimes be very complicated and difficult. A female prototype from the book The Unwomanly Face of War cried during the conversation with me, and some time after that I received a package from her with reports of her military service and a message: ‘I told you this so you could understand how hard it was for us. But we will not write about that in the book. In the book, my girl, we are going to write an absolutely different thing.’ She allowed such attitude because of my young age, I was only 30. There was a certain patriotic standard, and everyone had to meet it.

“Some women, whose stories I published in Zinky Boys, were mobilized by generals. Party workers sued me. One story is very painful for me. I met one woman when she was keeping vigil by the coffin of her son, just delivered from Afghanistan. She told me what she thought of it. When the huge coffin was dragged into her tiny room, she gave a heart-rending cry: ‘Tell’em! Tell’em that he was a carpenter who was made to repair generals’ summer houses for half a year! Who was never taught to shoot and throw grenades! And who was sent to that war, where he got killed in a month!’ And then she was among those suing me. She had been used by the generals. It hurt me to hear her say, ‘I don’t need your truth, I need a hero son.’ Suffering has no justification. There is only one way out, to love people. I love this woman, and I realize that she was not able to sort things out on her own. Everything was so complicated. First they lied to her when they sent her son to that war. And then, when they dragged her to the court. This is the problem of our people, who are not responsible for themselves. This is the Soviet person, a mixture of prison and kindergarten.”

In 2000 the Polish newspaper Tygodnik Powszechny organized a “Trial of the 20th Century.” The defendant was no one else but the 20th century, while the Polish intellectuals sued. Who do you think should be a judge in the case of events described in your books? Who has to answer for them?

“Each evil deed had its concrete doer. But in our society the victims always remain while the tormentors vanish into thin air. There have been lots of suicides, committed by people for the fear that their children and grandchildren would learn about what they had done before. The hierarchy shifts the blame on all petty executives, from top to bottom. The communist party was condemned, but not the idea. We must find the doers, those old ladies and gentlemen.

“I remember one revealing story about a woman who gave birth to a child in a prison camp. She told how cruelly the children were treated, because their parents were enemies of the people. One of such officers was an exceptionally cruel woman. This mother and her child suffered a lot at her hands. The mother swore to herself that if she were to survive, she would find her torturer by all means. She just wanted to look her in the eye. And finally, in the years of perestroika, she went to that camp settlement and found the officer, who by the time was in her nineties. First the ‘ward’ would not even let her in, then she began to explain: ‘I don’t remember, you were all alike. We had instructions and did as we were told.’ Then she began to complain: ‘My son drinks, my husband passed away, I get a tiny pension, I have pains in my stomach.’ Post factum: everyone is eventually unhappy, both the victims and the executors. However, I am convinced that evil must be punished. There should be a trial of the party, of concrete performers for concrete actions. Otherwise we will never get out of it. Who should sue? The victims and, of course, the elite.”

In your dialogs with Paul Virilio you said that “Chornobyl is not only an event in time, but also an event in history, and this catastrophe will give rise to philosophers.” How much do you think has this catastrophe changed man’s essence and human culture?

“When after the Second World War everyone learned about the Holocaust, about the killing of five million people only for being Jewish, Europe’s intellectuals said, ‘how can you write poems or listen to music after Auschwitz?’ [‘To write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric,’ words by Theodore Adorno. – Ed.]. How can you live on after that? But people learned to live on. However, something stopped them from realizing the scope of the Chornobyl disaster. First they said that ‘it’s all those messy Russians’ fault.’ But then, how can you account for Fukushima? A similar drama in an advanced nation. I visited Japan a few years prior to Fukushima. It is a different country, a different, technological civilization. And they also told me: ‘Such a thing could only have happened to you Russians. We have everything under control.” But it turns out that they had everything under control up to a magnitude 8.9-strong earthquake. But nature is unpredictable. Who knew that the magnitude of the quake would reach 9.0, exceeding the expected strength by 0.1? In Japan this information was also closed, the government pretended that everything was okay. Like in Chornobyl, kamikaze cleanup workers were dying in Japan, too. But they were paid well, this is the difference. In the USSR they used young soldiers, kicking them into the street afterwards. In Japan this work was done by older men, and the money was left to the families. This is an example of neat relationships, but does the world know of it? Both Chornobyl and Fukushima remain uninterpreted. But I think that these catastrophes will get people thinking. We must re-interpret the civilizational questions. Are we following the right path? What is our relationship with nature? But this requires a global revamping, for which man is not ready yet.”

You use a general term for all your protagonists, “the Soviet person.” Talking with Belarusian journalists one can hear that Belarus does not exist in terms of identity. Instead, there is the Belorussian Soviet Socialist Republic. An average Belarusian will not know the history of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, for instance. What do you think about it? Is identity restoration in Belarus or elsewhere on the post-Soviet territory possible?

“We have lost a lot of time. We could have created a state, national philosophy, history. But we were a hundred years too late. Who is there to do this titanic work? Today the milieu of patriotic-minded individuals is like a ghetto. There are a few intellectuals, although young people often join in. But as the young grow up, they take to the streets in protest actions (we are Belarusian!), then they are kicked out of the university, and then they emigrate to Europe. This cycle is well calculated. Lukashenka has committed this crime three times. And we are again waiting for the next generation, but the story repeats. Belarus needs experts. And I don’t know who will work on Belarusian self-identity. The older generation of writers are passing away. This is a big question.”

You were born in Ivano-Frankivsk [Alexievich’s father, a village teacher, was sent there to do his military service; her grandmother was Ukrainian. – Ed.]. Did it influence your self-awareness? What are your memories of those times?

“The memories of an endlessly hard life. I was born soon after the war. There were all those cripples rattling their crutches… I have a distinct memory of the blossoming orchards, apple and pear trees, and soft soil, where your feet were sinking deep. I also remember the markets and the smell of poverty: lard and bread. I remember the beautiful language and my granny in a white blouse whitewashing the house. This is where my interest in people stems from. I remember long talks, the sobriety of life, and the trust towards life. Therefore you will find no bombast in my books: because I remembered the intonation my grandma and other farm women spoke with. Endless pain and endless sorrow.

“I remember our abject misery. My grandma was a woman of very modest means. I remember we were pushing a wheel cart with a bag of cereals, wheat, and sugar. Ridiculously little, compared to how much she had worked for it. No one sold anything to Soviet officers. At the age of two I nearly starved to death: there was no food for me. Then my father went to a nunnery to ask for food. His colleagues helped him over the fence (he might not enter through the front door), and he went straight to the abbess. He tried to touch her: ‘You serve God. You may kill me, you may do whatever you want, but a child is dying…’ She said to him: ‘Get lost, I do not want to ever again set my eyes on you. But your wife may come. For two months I will give her half a liter milk a day.’ I was fed that goat’s milk, and so I survived.

“When the Japanese made a movie after my books, they wanted to film that convent. We went there only to find a seminary. Of course, the abbess was long gone…”

In an interview to the Voice of America you said that if someone has made Belarus into what it is now, it was Lukashenka rather than the nation’s intellectuals. Why did it so happen that you were not heard? Does today’s Belarus have intellectuals who can make themselves heard?

“No it doesn’t. There is no national feeling like in the Baltic countries. As soon as the perestroika began, they said, I’m Lithuanian, I’m Estonian, I’m Lettish. Although they are not very numerous, nations of 1.5 to 3 million. We thought that after the perestroika Belarusians, too, would want to know their history and culture. But our people were immediately overwhelmed with the material. Buy a car, have a holiday in Egypt, get a visa, build a villa… These national issues matter to a very narrow circle of people. Even as I listened to our boys [Belarusian writers. – Ed.], I noticed that they were talking about the Belarus they had in their heads. You want to change it, but it’s non-existent! I come to a village, and the local guys tell me: ‘Freedom? What freedom? I have a house outside the city. Go have a look at the local food store: three sorts of sausage, bananas, vodka to suit any palate. Isn’t this freedom? Why don’t you like Lukashenka? We are paid pensions, living has become better, our children drive their own cars…’ As long as Lukashenka has this contract with the population, nothing is going to change. I don’t know where he takes the money, from contraband or guns running, but he earns pretty enough.”

Do you believe in a Belarus without Lukashenka?

“Well, he is mortal, so sooner or later he has to go. I think that is going to be a hard time. While people around us have been learning to live under new circumstances, we have been preserved in a time warp. We have a sort of imperial socialism.”

You say that you chose the genre of human voices for your books, and at the same time you proclaim that a modern person ended up one on one with the world. Obviously, it is about marginalization of personality, which in its turn, leads to a deficit of outstanding personas in politics, art, and culture. Do you feel the crisis of figures, in Europe in particular?

“Europe has a higher cultural level. This work was done by many generations. There is a dictatorship of small, mass person. General philosophic crisis can be observed as well. The civilization was built on a paradigm which is going through a crisis right now. It became a revelation for me that the post-Soviet space turned out to be so ‘bare.’ I do not know whether you have such figures, but Belarus does not. There were barricade figures of the fight. But there are no simply spiritual gurus. All intellectual life is narrowed to a thought that Lukashenka should be removed. Go away, Putin! In your case, it is Yanukovych. And we do not even notice that we make no headway, that the society is getting dumber. Actually, this is not a mission of humankind. We all have a higher mission… this is a mystery, a meaning of life for all of us. And we are hostages of the struggle culture, it is about death on barricades. I came back to Belarus. Where are the people? Everyone emigrated. I remember, we started perestroika, Memorial movement, powerful processes together… Now, everybody is gone. Emptiness appeared in the post-Soviet space.”

We know that you are working on the final part of your pentalogy about the Red person. What is the Red person like?

“It is a mixture of prison and kindergarten. It is a person who entrusted the state with everything, who cannot make a choice, live life on their own. But this person cannot be blamed for this, because nobody taught them otherwise since early childhood. People cannot be set free in one day. This is not Swiss chocolate or Finnish paper. The process of human creation is very long. And we have gotten into an interim period. I called the last book from the Red Empire series Second-Hand Time for a reason. Second-hand ideas, second-hand words, second-hand clothes are typical for both the nation and the government.

“But the philosophy of a human will change. And now I explore a person without a Red idea, a person who lives their own life. Existentially. I plan to write a hundred stories about love and death. I will try to tell about a Slavic person, who tries to live without an idea, be it communist or any other, and who looks for higher purposes in life. We do not have culture and literature of happiness. And this is something we should learn, how to live for ourselves, and not only for the sake of ‘the great homeland.’ I will learn how to be happy too. Despite everything I do, I love life. It has plenty of beautiful things – love, nature, and for me – my little granddaughter. This is the flow of life. One should be able to come to their senses, stop, and think: what do I live for?”