Den’s school of caricature

And the fate of civic satire in Ukraine

The murder of cartoonists and employees of the Paris satirical periodical Charlie Hebdo became a sad reason to think about the role of caricature in the modern society and media environment. Sharpness, approach, styles, schools, and respectively, response gained by works of Ukrainian and foreign artists can be compared. But there are cartoonists, whose drawings are beyond the limits of nationality and time. “Great artists’ drawings are stories without words, a sort of visual text,” says Russian cartoonist Viktor Bogorad, who has been contributing to Den/The Day for almost a year. This was characteristic of Anatolii Kazansky, Den’s artist since 1996, who worked until the last day of his life. “According to many, he was the best cartoonist of Ukraine,” writes the online periodical Kyivsky Kalendar (“The Kyiv Calendar”). Another example of the Ukrainian caricature’s heritage is the Kyiv-based club Archihum, founded in 1983. By the way, Kazansky was one of its founders.

Over 30 years has passed, two out of four Archihum’s founders passed away (Yurii Kosobukin and Anatolii Kazansky). Exhibition started attracting increasingly fewer visitors, especially young ones. Lately, two cartoon contests have been organized annually by the Association of Cartoonists. Periodically such contests are also held in Kherson and Poltava. But past year, an exhibition of cartoons from an international contest was prohibited in Kherson due to their “intolerance.” The exhibition was called “Devil’s Gas Station” and was a response to Russia’s annexation of Crimea and armed invasion in Donbas. This is a sad paradox. So, a question arises: what does civic satire lack, demand or supply?

BETWEEN CARICATURE AND A POOR EXCUSE

“Caricature as the reflection of negative processes that take place in our country has been in decay in Ukraine during the past four or five years, and demand for it in mass media is extremely low (even though demand in the society is quite strong). Speaking of the state of affairs of political caricature in Ukraine, it seems to me that it has not stopped existing, but as the song goes ‘it lay low for a while,’” thinks artist and Den/The Day’s contributor Ihor LUKIANCHENKO. “After the crisis of 2008, the majority of newspapers and magazines that were the main platform for the existence of caricature, shut down. The closing down of Perets (“Pepper”) became symbolic. The remaining printed mass media are not in the best shape to be able to pay for exclusive cartoons. Additionally, we do not have strong historical traditions in humor in general and caricature in particular, unlike England or France, for example. The majority of newspaper owners and editors cannot relate to humor and satire, or they do not possess the sense of humor to a necessary extent.”

Or this humor is demonstrated to readers in a perverted form, for example, specific politicians in almost pornographic poses. But this is the “yellow,” tabloid level, and there is much finer manipulation of caricature, when nobody really offends anyone, but fearful senses are being implanted in society. For example, an exhibition of cartoons was displayed at the Verkhovna Rada in 2011. Among the drawings were NATO’s West for Ukraine or an image of a liner called The EU’s Aid, which was sinking a small boat, Ukraine. This is how the delayed action bomb was planted, and the country’s further geopolitical vector was imposed on the public with the help of similar tricks. Those who absolutely disagreed with turning “back to USSR” were mocked. The servility of Ukrainian journalism also laid foundation for the current situation in Donbas and Crimea. Maybe, manuscripts do not burn, but archives do pretty good, especially when it is necessary to change colors and join a different political wing. And what about the readers? Will they take it?

“An artist has to occupy a corresponding spot in society to be able to reveal his civic stand. But in our society, a cartoonist performs the role of an illustrator, who is assigned with a task to portray certain things in specific light,” head of the Association of Cartoonists of Ukraine Kostiantyn KAZANCHEV comments to The Day. “They still cannot abandon the Soviet system in the negative sense. Petty officials, as well as oligarchs, still have a ‘leader syndrome’ and can throw tantrums because someone dared to portray them in a caricature. And since the majority of mass media are platforms that belong to both groups, it means that if you are drawing a caricature for one newspaper, you are encroaching upon ‘somebody else’s territory.’ There should be no untouchables, but the caricature must be restored to its normal sense, instead of some degraded version that is often demanded now.”

TO PERETS OR THE NEW YORKER?

The fate of Ukrainian political caricature has had its rises and falls. But the government has never understood or supported it. Unfortunately, the absence of self-irony shows the inability to accept criticism, and therefore, to abandon the old system. According to Kazanchev, one of the examples took place in 2006, when the then president Viktor Yushchenko planned to visit an exhibition of political cartoons, which was organized by the Association. It could be a signal for the post-revolutionary society. But Yushchenko never showed up. And as it is known, history moves down a spiral.

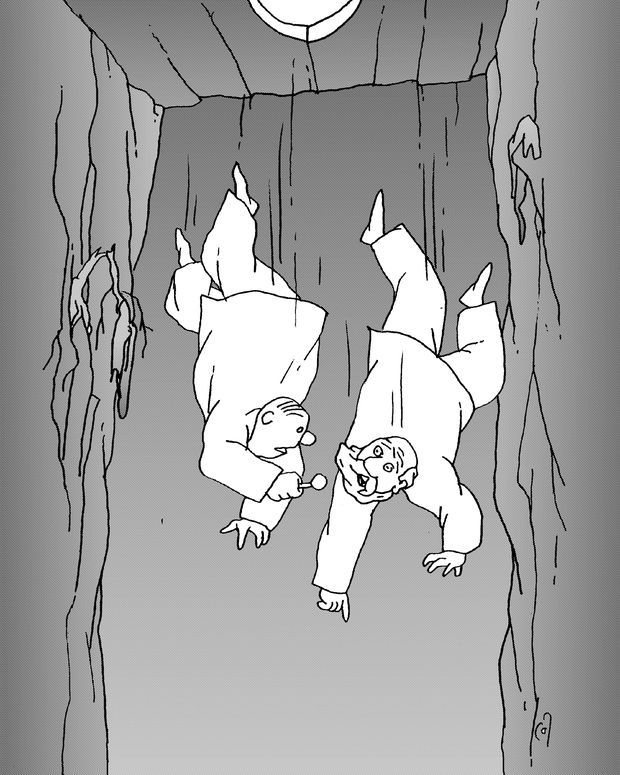

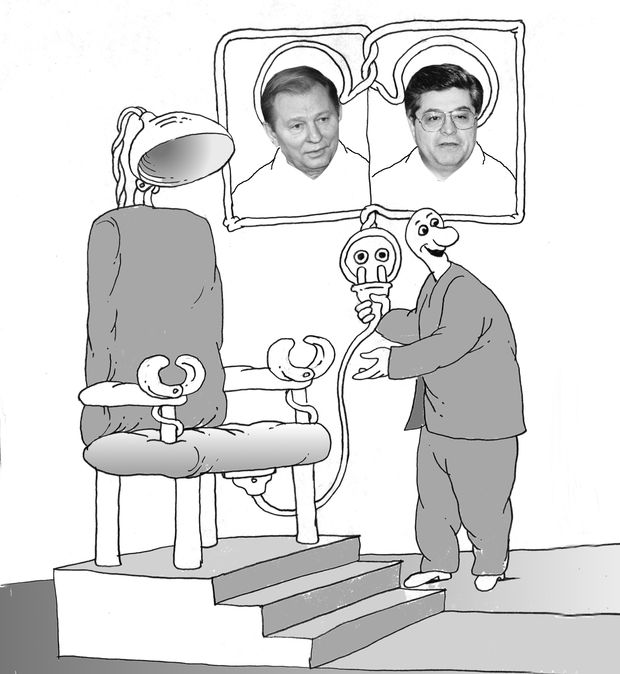

THIS WAS DRAWN BY THE INGENIOUS CARTOONIST ANATOLII KAZANSKY BACK IN 1998, AS A RESPONSE TO THE CURRENT EVENTS. YET TALENTED WORKS ARE TIMELESS, AND THIS CARTOON, SADLY, BECAME A PROPHECY. THE CLAN OLIGARCHIC SYSTEM, CREATED BY KUCHMA, WAS NOT DESTROYED BY TWO MAIDANS. AN INCREDIBLY HIGH PRICE WAS PAID, THE LIVES OF THE VICTIMS OF MAIDAN AND THE WAR, WHILE THE “SYSTEM’S” ARCHITECT REPRESENTS UKRAINE AT “PEACE NEGOTIATIONS.” THIS IS DEN’S SCHOOL. IT IS DIFFERENT THAN THAT OF CHARLIE. IT IS ACUTELY SOCIAL, PROPHETIC, AND PHILOSOPHICAL / Sketch by Anatolii KAZANSKY from The Day’s archives, 1998

Lukianchenko thinks that a carte blanche for a full-time cartoonist is very rare. Kazanchev complains that we do not have cartoonists with their own column in printed media, which is normal in leading civilized countries. However, both agree that a lot of our artists are successful in foreign cartoon markets, they win prizes at numerous caricature contests, their works are printed in newspapers and magazines. But besides these contests, there are also online platforms and virtual banks of cartoons, where a periodical can choose and purchase a work they like, and users can view visual history of the present and the past. After all, if a cartoonist is an artist, and not a craftsman, he simply will not be able to keep quiet in his work about what is unraveling in his sight. The audience switched to other visual tools – infographics, demotivators, collages, because they were bored with the old-fashioned cartoons. Perets of the last years is not something modern society is interested in. One must think several steps (centuries?) ahead to capture the reader’s interest, and then caricature will be interesting. And here Kazansky’s drawings come to mind again. As Den/The Day’s editor-in-chief Larysa Ivshyna wrote in a foreword to his cartoons album, “His drawings expanded time.” Caricature that does not chase the pettiness of the moment can last very long with a philosophical interpretation. A lot depends on the approach and preconditions. If his drawings are compared to the Western cartoons, they are on the level of the famous New Yorker.

SEEN FROM THE RUSSIAN SIDE

The roots of Ukrainian cartoon go back into the Soviet school. The Ukrainian and Russian cartoons had developed within a common paradigm. Yet, as always, there were official “champions of truth” and unofficial, avant-garde artists, e.g., the same Archihum from Kyiv.

“In the Ukrainian SSR, just as anywhere in the entire Soviet Union, there were two distinct ‘troops’ of cartoonists,” reminisces Viktor BOGORAD. “The official ones were printed in the Ukrainian Perets and in our Krokodil (“Crocodile”) and were well-paid (Krokodil paid 300 rubles for the cover and 80 rubles for a picture, while a civil engineer’s average monthly salary was 120 rubles). There were other artist, avant-gardists, who received loads of international awards beginning somewhere in 1968. The Krokodil artists even wanted to ban participation in those international contests, as there was a sort of latent, secret censorship in the industry. However, after the collapse of the USSR the Ukrainian and Russian cartoonists did not follow separate paths. We have published an album by Yurii Kosobukin, and an album by Volodymyr Kazanevsky is to follow soon. Last year I was invited to visit the 30th anniversary of the Kyiv cartoonist club Archihum, we have time-honored ties. This is a professional group. Ukrainian artists are indeed well represented in our country, and as far as technique and approach goes, their works do not differ from Russian or Western ones.

“In the Soviet time the Polish satirical magazine Szpilki (“Pins”) was very popular in our country. By the way, they often published drawings by Georges Wolinski (the assassinated French cartoonist at Charlie Hebdo). Those were wonderful pictures… I think they have influenced me, too. However, I did not know Wolinski in person. Thanks to this magazine, cartoonists were able to learn about other caricatures, different from Krokodil style. Often they reprinted high-brow cartoons for white collars from The New Yorker. It was a whole another approach to the interpretation of satirical and humorist caricature. Krokodil was busy ridiculing individual faults, its characters were very concrete. For instant, if an official was bad, it was just this very official, and all the others were saints. No generalizations, we only have individual faults. Conversely, the pictures printed by Szpilki were an attempt to go into human psychology. This opened the boundaries. For the Russian cartoon of that time it was not typical, artists had entirely other goals.”

A HARD ACT TO FOLLOW

The goals set by Anatolii Kazansky for himself were entirely different. “Anatolii Kazansky, who worked for Den, set a very high goal, which was later a benchmark for all the cartoonists working with our periodical. In this sense, we can speak of Den’s school of cartoon. So, the key demand you set before yourself drawing for Den is at least to try to reach this level, if not surpass it,” tells Lukianchenko. “Looking at the period when Kazansky worked for Den, its main difference was that his cartoons have been inimitable in terms of style and message. There was hardly another periodical that could compete with Den’s level of illustrations.” According to Lukianchenko, during wars, revolutions, political conflicts, and social disasters the demand for the cartoon, and interest in it, increased 10 times, and those were just the conditions in which the cartoon thrived and evolved. So, let us wait and see what new talents, brought up by Den’s school of cartoon, will be able to grow up in our media space.