Unknown Les Lozovsky

How the artist, belonging to Mykhailo Boichuk’s school, combined in his creative career the art of “tenderness” with that of “challenge”

We have rather vague and yet contradictory data on the origins of Oleksandr Lozovsky. Dictionary of Artists of Ukraine gives the date of his birth as August 1900, while another source adds that it occurred in Pohrebyshche county of Kyiv province. As Lozovsky’s friend of student years, fellow artist Hryhorii Khyzhniak stated, “the artist never talked about his parents, and nobody had any hard information about his origins and early years.”

As a 15-year-old youth, he entered Kyiv Higher Elementary School, at the same time learning the basics of painting at the city’s art school, with one of his teachers there being “the good master” Mykhailo Kozyk. It was likely Kozyk’s advice that prompted Lozovsky to continue his studies at the Stroganov School of Art in Moscow.

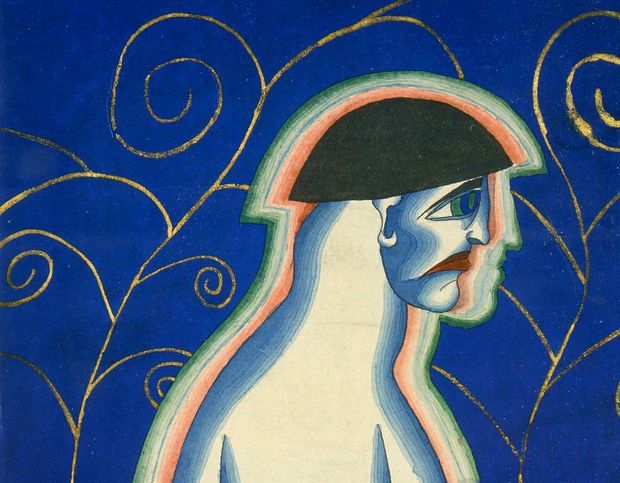

The Ukrainian Academy of Arts was solemnly inaugurated in Kyiv on November 22, 1917. We see Lozovsky’s name among the first three students of Heorhii Narbut’s workshop, along with Adamska and Burk. Artist Mykola Burachek called them “the most faithful of Narbut’s disciples.” From his first teacher, the young man picked up a meticulously precise style of composition; he developed a monumentally concise painting style of his own, creating the personal “Lozovsky font” (used in covers of Pavlo Tychyna’s collection Plow, works by Stepan Vasylchenko, and numerous sheet music albums). At the same time, Lozovsky was actively involved with publishing unauthorized comic magazine Eleas, creating a series of watercolors for it, which have been partially preserved in the collection of the National Art Museum of Ukraine (namely, How Should a Futurist Look Like and A Portrait of My Soul).

General Anton Denikin’s White forces seized power in Kyiv on August 31, 1919. Not recognizing the academy as a state institution, they evicted it from its premises. The First Review Exhibition of the academy’s students was opened at its new home in Heorhiivsky Lane on March 10, 1920, displaying Lozovsky’s easel sheets Malachite and Memento Mori (the originals of these works were rediscovered by historian Serhii Bilokin in the 1980s).

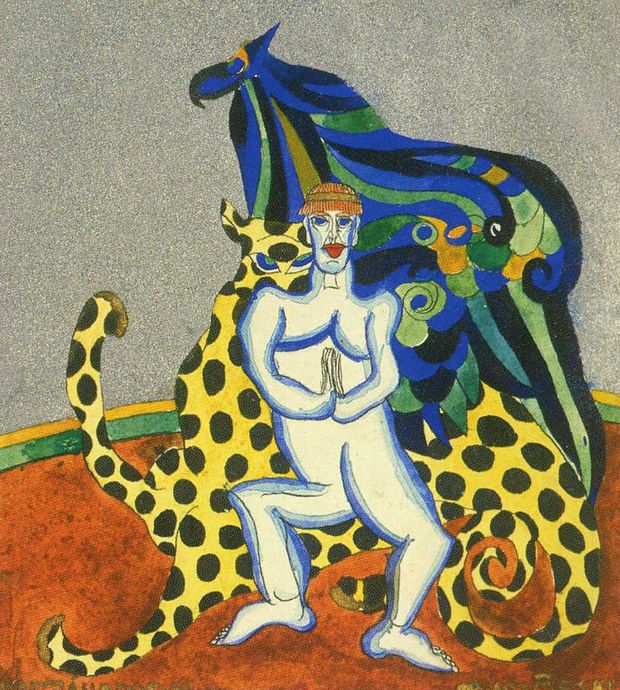

Following the death of his teacher in May 1920, Lozovsky transferred to the workshop of monumental art professor Boichuk, thus inaugurating a new period of the young graphic artist’s creative career. Lozovsky adopted Boichuk’s view that the artists needed to combine elements of composition into a coherent whole, developing them according to a chosen scheme. His last two years’ works were meant for books and are difficult to imagine in any other context. They are monumental, with a clear and concise line of font. Lozovsky’s covers of books and magazines feature clear design, beauty and clarity of fonts, decorative color solutions. The most interesting are his covers for Tychyna’s collections Instead of Clarinets and Octaves and Sunny Clarinets (1920).

Fall of 1921 saw the academy opening the Second Review Exhibition, where Lozovsky presented eight works. In addition to book cover for Yakov Tugendkhold’s French Art of the 19th Century, sheet of music to the song Chamomile Blossoms on a Hill and covers for three collections of Tychyna’s verses, the artist exhibited two easel works done on the board with tempera paints: portraits of Hryhorii Skovoroda and Vladimir Lenin. Reviewing this exhibition, critic Lev Dintses emphasized the diversity of Lozovsky’s talent, finding in his works “soft tenderness coexisting with special solemnity, somewhat like what we see in the Novgorod icons.”

How Should a Futurist Look Like

Lozovsky was never an “orthodox Boichukist.” Caustic and sharp-tongued, he criticized his teacher and often failed to attend his workshop. He also did not take part in painting chambers of the Fifth All-Ukrainian Congress of Soviets in Kharkiv and Kyiv Opera House, even though Oksana Pavlenko stated that they were part of the curriculum rather than regular commercial orders.

Because the statute of the academy allowed its students to sign up with two professors at a time, Lozovsky began attending the theater arts workshop of Vadym Meller without stopping his training under Boichuk.

As Meller’s student Natalia Aleksieieva-Horbunova (she was expelled from the Institute of Plastic Arts in 1923, as “a spawn of bourgeois capitalists” who “wormed her way into our proletarian school”) recalled: “In 1922 Lozovsky was our monitor who was also responsible for the workshop’s external relations. He was often late to our lessons, entering when the sitter was already posing; he quickly unrolled his long scarf, took off his smart sheepskin coat and, having shaken his forelock, got to work. We draw very similar geometrical forms and tried to get nature fit into them. We long pondered on and tried to compose them as well. In fact, these lessons were practical exercises in composition, which were so peculiarly organized by Meller.”

However, the studies did not produce any tangible results, as Lozovsky’s time on Earth was ending... He was strangled in his own home under unexplained circumstances on the night of March 22, 1922.

…Meanwhile, the exhibition of modern Ukrainian graphics held by the Association of Independent Ukrainian Artists in Lviv in 1932 had critics praising books designed by Lozovsky.